Devina Angeline Wiratama / 0350824

Typography / Bachelor of Design (Hons) in Creative Media

Task 1: Exercises

Jump Link

- Lectures

- Instructions

- Exercise 1 - Type Expression

- Exercise 2 - Type Formatting

- Feedback

- Reflections

- Further Reading

- Typography

- Home

LECTURES

1. WEEK 1 / Introduction & Briefing

Font: a font refers to the individual font or weight within the typeface.

Ex: Georgia regular, Georgia italic, and Georgia bold.

Typeface: a typeface refers to the entire family of fonts/ weights that share

similar characteristics/ styles. Ex: Georgia, Arial, Times New Roman,

Didot, and Futura.

a. Typography: Development and Timeline

Early letterform development: Phoenician to Roman

Phoenicians (like other Semistic peoples), wrote from right to left. The Greeks developed a style of writing

called 'boustrophedon' (how the ox ploughs) → the lines of text read

alternately from right to left and left to right. They also changed

the orientation of the letterforms. Greek like the Phoenicians,

didn't use letter space or punctuations. Latter or the Greeks would

move to strictly left-to-right writing.

Fig 1a.2 / Writing Direction of Greeks, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

Fig. 1a.3 / Greek fragment, stone engraving (Date

unknown), Week 1 (08.27.2021)

Etruscan (and then Roman)

carvers working in marble painted letterforms before inscribing

them. Certain qualities of their strokes-a change in weight from

vertical to horizontal, a broadening of the stroke at the start and

finish-carried over into the carved letterforms.

Fig. 1a. 5 / Phoenician to Roman (Flip horizontal → flip 90°), Week 1 (08.27.2021)

b. Hand script from 3rd - 10th century C.E

Square capitals

were the written version that can be found in Roman monuments.

These letterforms have serifs added to the finish of the main

strokes. The variety of stroke width was achieved by the reed pen

held at an angle of approximately 60° off the perpendicular.

A

compressed version of square capitals, rustic capitals

allowed for twice as many words on a sheet of parchment and took

far less time to write. The pen or brush was held at an angle of

approximately 30° off the perpendicular. Although rustic capitals

were faster and easier to, they were slightly harder to read due

to their compressed nature.

Both square and rustic

capitals

were typically reserved for documents of some intended

performance. Everyday transactions, however, were typically

written in Roman cursive

hand in which forms were simplified for speed. We can see here the

beginning of what we refer to as lowercase letterforms.

Uncials

incorporated some aspects of the Roman cursive hand, especially in

the shape of the A, D, E, H, M, U, and Q. 'Uncia’ is Latin for a

twelfth of anything; as a result, some scholars think that uncials

refer to letters that are one inch (one-twelfth of the foot) high.

It might, however, be more accurate to think of uncials simply as

small letters. The board forms of uncials are more readable at

small sizes than rustic capitals.

A

further formalization of the cursive hand, half-uncials

mark the formal beginning of lowercase letterforms, replete with

ascenders and descenders, 2000 years after the origin of the

Phoenician alphabet.

Charlemagne, the first unifier of Europe since the Romans, issued an edict

in 789 to standardize all ecclesiastical texts. He entrusted this

task to Alcuin of York, Abbot of St. Martin of Tours. The monks

rewrote the text using both majuscules (uppercase), minuscule,

capitalization, and punctuation which set the standard for

calligraphy for a century.

Fig. 1b.6 / C. 925: Caloline Miniscule, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

c. Blackletter to Gutenberg's type

With the dissolution of

Charlemagne's empire came regional variations upon Alcuin's

script. In Northern Europe, a condensed strongly vertical

letterform know as blackletter or texture gained popularity.

In the south, a rounder more open hand gained popularity,

called 'rotunda'. The humanistic scripting in Italy is based

on Alcuin's minuscule.

Gutenberg's skills marshalled them all to build pages that

accurately mimicked the work of the scribe's hand -

Blackletter of northern Europe. His type mould required a

different brass matrix, or negative impression, for each

letterform.

d. Text type classification (Dates of origin approximated to the

nearest quarter-century).

Typeforms have developed in response

to prevailing technology, commercial needs, and esthetic trends.

Certain models have endured well past the cultures that spawned

them. The following Typeform classification here, based on one devised by

Alexander Lawson only covers the main form of text type.

1450 BlackLetter

The

earliest printing type, its forms were based upon the hand-copying

styles that were then used for books in northern Europe. Examples:

Cloister black, Goudy text

1475 Old-style

Based

upon the lowercase forms used by Italian humanist scholars for book

copying (themselves based upon the ninth-century Caroline minuscule)

and the uppercase letterforms found inscribed on Roman ruins, the

forms involved away from their calligraphic origins over zoo years, as

they migrated across Europe, from Italy to England. Examples: Bembo,

Caslon, Dante, Garamond, Janson, Jenson, Palatino

1500 Italic

Echoing contemporary Italian

handwriting, the first italics were condensed and close-set, allowing

more words per page. Although originally considered their own class of

type, italics were soon cast to complement Roman forms. Since the

sixteenth century, virtually all text typefaces have been designed

with accompanying italic forms.

Fig. 1d.3 / 1500 Italic, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

1550 Script

Originally attempt to replicate

engraved calligraphic forms, this class of type is not entirely

appropriate in lengthy text settings. In shorter applications,

however, it has always enjoyed wide acceptance. Forms now range from

the formal and traditional to the casual and contemporary. Examples:

Kuenstler script, Mistral, Snell Roundhand.

Fig. 1d.4 / 1550 Script, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

1750 Transitional

A

refinement of old-style forms, this style was achieved in part because

of advances in casting and printing. Thick to thin relationships were

exaggerated, and brackets were lightened. Examples: Baskerville,

Bulmer, Century, Time Roman

1775 Modern

This

style represents a further rationalization of old-style letterforms.

Serifs were unbracketed, and the contrast between thick and thin

strokes was extreme. English versions (like a bell) are also known as

Scotch Romans and more closely resemble transitional forms. Examples:

Bell, Bodoni, Caledonia, Didot, Walbaum

1825 Square serif/ Slab serif

Originally heavily bracketed serifs

with little variation between thick and thin strokes, these faces

responded to the newly developed needs of advertising for heavy types

in commercial printing. As they evolved, the brackets were dropped.

Examples: Clarendon, Memphis, Rockwell, Serifa

1900 Sans Serif

As

their name implies, these typefaces eliminated series altogether.

Although the forms were first introduced by William Caslon IV in 1816,

their use did not become widespread until the beginning of the

twentieth century. Variation tended toward either humanist forms (Gill

sans) or rigidly geometric (Futura). Occasionally, strokes were hard

to suggest the calligraphic origins of the form (optima). Sans serif

is also referred to as grotesque (from the German word Grotesk) and

Gothic. Examples: Akzidenz Grotesk, Grotesk, Gill sans, Franklin

gothic, Frutiger, Futura, Helvetica, Meta, News Gothic, Optima,

Syntax, Trade Gothic, Univers.

1990 Serif / Sans serif

A

recent development, this style enlarges the notion of a family of

typefaces to include both serif and sans serif alphabets (and often

stages between the two). Examples: Rotis, Scala, Stone

a.

Typography: Basic / Describing Letterforms

Font: a font refers to the individual font or weight within the typeface.

Ex: Georgia regular, Georgia italic, and Georgia bold.

Typeface: a typeface refers to the entire family of fonts/ weights that share

similar characteristics/ styles. Ex: Georgia, Arial, Times New Roman,

Didot, and Futura.

Early letterform development: Phoenician to Roman

Phoenicians (like other Semistic peoples), wrote from right to left. The Greeks developed a style of writing called 'boustrophedon' (how the ox ploughs) → the lines of text read alternately from right to left and left to right. They also changed the orientation of the letterforms. Greek like the Phoenicians, didn't use letter space or punctuations. Latter or the Greeks would move to strictly left-to-right writing.

Fig 1a.2 / Writing Direction of Greeks, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

Fig. 1a.3 / Greek fragment, stone engraving (Date unknown), Week 1 (08.27.2021)

Etruscan (and then Roman)

carvers working in marble painted letterforms before inscribing

them. Certain qualities of their strokes-a change in weight from

vertical to horizontal, a broadening of the stroke at the start and

finish-carried over into the carved letterforms.

Fig. 1a. 5 / Phoenician to Roman (Flip horizontal → flip 90°), Week 1 (08.27.2021)

b. Hand script from 3rd - 10th century C.E

Square capitals

were the written version that can be found in Roman monuments.

These letterforms have serifs added to the finish of the main

strokes. The variety of stroke width was achieved by the reed pen

held at an angle of approximately 60° off the perpendicular.

A

compressed version of square capitals, rustic capitals

allowed for twice as many words on a sheet of parchment and took

far less time to write. The pen or brush was held at an angle of

approximately 30° off the perpendicular. Although rustic capitals

were faster and easier to, they were slightly harder to read due

to their compressed nature.

Both square and rustic

capitals

were typically reserved for documents of some intended

performance. Everyday transactions, however, were typically

written in Roman cursive

hand in which forms were simplified for speed. We can see here the

beginning of what we refer to as lowercase letterforms.

Uncials

incorporated some aspects of the Roman cursive hand, especially in

the shape of the A, D, E, H, M, U, and Q. 'Uncia’ is Latin for a

twelfth of anything; as a result, some scholars think that uncials

refer to letters that are one inch (one-twelfth of the foot) high.

It might, however, be more accurate to think of uncials simply as

small letters. The board forms of uncials are more readable at

small sizes than rustic capitals.

A

further formalization of the cursive hand, half-uncials

mark the formal beginning of lowercase letterforms, replete with

ascenders and descenders, 2000 years after the origin of the

Phoenician alphabet.

Charlemagne, the first unifier of Europe since the Romans, issued an edict

in 789 to standardize all ecclesiastical texts. He entrusted this

task to Alcuin of York, Abbot of St. Martin of Tours. The monks

rewrote the text using both majuscules (uppercase), minuscule,

capitalization, and punctuation which set the standard for

calligraphy for a century.

Fig. 1b.6 / C. 925: Caloline Miniscule, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

Fig. 1b.6 / C. 925: Caloline Miniscule, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

c. Blackletter to Gutenberg's type

With the dissolution of

Charlemagne's empire came regional variations upon Alcuin's

script. In Northern Europe, a condensed strongly vertical

letterform know as blackletter or texture gained popularity.

In the south, a rounder more open hand gained popularity,

called 'rotunda'. The humanistic scripting in Italy is based

on Alcuin's minuscule.

Gutenberg's skills marshalled them all to build pages that

accurately mimicked the work of the scribe's hand -

Blackletter of northern Europe. His type mould required a

different brass matrix, or negative impression, for each

letterform.

d. Text type classification (Dates of origin approximated to the

nearest quarter-century).

Typeforms have developed in response

to prevailing technology, commercial needs, and esthetic trends.

Certain models have endured well past the cultures that spawned

them. The following Typeform classification here, based on one devised by

Alexander Lawson only covers the main form of text type.

1450 BlackLetter

The

earliest printing type, its forms were based upon the hand-copying

styles that were then used for books in northern Europe. Examples:

Cloister black, Goudy text

1475 Old-style

Based

upon the lowercase forms used by Italian humanist scholars for book

copying (themselves based upon the ninth-century Caroline minuscule)

and the uppercase letterforms found inscribed on Roman ruins, the

forms involved away from their calligraphic origins over zoo years, as

they migrated across Europe, from Italy to England. Examples: Bembo,

Caslon, Dante, Garamond, Janson, Jenson, Palatino

1500 Italic

Echoing contemporary Italian

handwriting, the first italics were condensed and close-set, allowing

more words per page. Although originally considered their own class of

type, italics were soon cast to complement Roman forms. Since the

sixteenth century, virtually all text typefaces have been designed

with accompanying italic forms.

Fig. 1d.3 / 1500 Italic, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

1550 Script

Originally attempt to replicate

engraved calligraphic forms, this class of type is not entirely

appropriate in lengthy text settings. In shorter applications,

however, it has always enjoyed wide acceptance. Forms now range from

the formal and traditional to the casual and contemporary. Examples:

Kuenstler script, Mistral, Snell Roundhand.

Fig. 1d.4 / 1550 Script, Week 1 (08.27.2021)

1750 Transitional

A

refinement of old-style forms, this style was achieved in part because

of advances in casting and printing. Thick to thin relationships were

exaggerated, and brackets were lightened. Examples: Baskerville,

Bulmer, Century, Time Roman

1775 Modern

This

style represents a further rationalization of old-style letterforms.

Serifs were unbracketed, and the contrast between thick and thin

strokes was extreme. English versions (like a bell) are also known as

Scotch Romans and more closely resemble transitional forms. Examples:

Bell, Bodoni, Caledonia, Didot, Walbaum

1825 Square serif/ Slab serif

Originally heavily bracketed serifs

with little variation between thick and thin strokes, these faces

responded to the newly developed needs of advertising for heavy types

in commercial printing. As they evolved, the brackets were dropped.

Examples: Clarendon, Memphis, Rockwell, Serifa

1900 Sans Serif

As

their name implies, these typefaces eliminated series altogether.

Although the forms were first introduced by William Caslon IV in 1816,

their use did not become widespread until the beginning of the

twentieth century. Variation tended toward either humanist forms (Gill

sans) or rigidly geometric (Futura). Occasionally, strokes were hard

to suggest the calligraphic origins of the form (optima). Sans serif

is also referred to as grotesque (from the German word Grotesk) and

Gothic. Examples: Akzidenz Grotesk, Grotesk, Gill sans, Franklin

gothic, Frutiger, Futura, Helvetica, Meta, News Gothic, Optima,

Syntax, Trade Gothic, Univers.

1990 Serif / Sans serif

A

recent development, this style enlarges the notion of a family of

typefaces to include both serif and sans serif alphabets (and often

stages between the two). Examples: Rotis, Scala, Stone

1. As with any craft that has evolved over 500 years, typography employs a number of technical terms. These mostly describe specific parts of the letterforms. It is a good idea to familiarize yourself with the lexicon. Knowing a letterform’s component parts make it much easier to identify specific typefaces.

Baseline: imaginary line the visual base of the letterforms

Median: imaginary line defining the x-height of letterforms

X-height: the heigh of the typeface in the lowercase 'X.

2. Stroke: Any line that defines the basic letterforms

3. Apex/ Vertex: the point created by joining two diagonal stems (apex above and vertex below)

Fig. 2a.1 / Baseline, Median, X-height, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

2. Stroke: Any line that defines the basic letterforms

Fig. 2a.2 / Stroke, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

3. Apex/ Vertex: the point created by joining two diagonal stems (apex above and vertex below)

Fig. 2a.3 / Apex or Vertex, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

4. Arm: Short strokes off the stem of the letterform, either horizontal (E, F, L) or inclined upwards (K, Y).

Fig. 2a.4 / Arm, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

5. Ascender: The portion of the stem of a lowercase letterform that projects above the median.

Fig. 2a.5 / Ascender, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

6. Barb: The Half-serif finish on some curved stroke.

Fig. 2a.6 / Barb, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

7. Beak: The half-serif finish on some horizontal arms.

Fig. 2a.7 / Beak, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

8. Bowl: The rounded form that describes a counter. The bowl may be either open or closed.

9. Bracket: The transition between the serif and the stem.

10. Cross Bar: The horizontal stroke in a letterform that joins two

stems together.

11. Cross Stroke: The horizontal stroke in a letterform that joins

two stems together.

Fig. 2a.11 / Cross Stroke, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

12. Crotch: The interior space where two strokes meet.

13. Descender: The portion of the stem of a lowercase

letterform that projects below the baseline.

Fig. 2a.13 / Descender, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

14. Ear: The stroke extending out from the main stem or body

of the letterform.

15. Em/ en: Originally referring to the width of an uppercase M,

and em is now the distance equal to the size of the typefaces (an em in 48

points, for example). An en is half the size of an em. Most often used to

describe em/en spaces ad em/en dashes.

Fig. 2a.15 / Em or en, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

16. Ligature: Character formed by the combination of two or more letterform.

Fig. 2a.16, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

17. Link: The stroke that connects the bowl and the loop of a

lowercase (G).

18. Loop: in some typefaces, the bowl is created in the descender of the lowercase (G).

19. Serif: The right-angled or oblique foot at the end of the stroke.

20. Spine: The curved stem of the (S).

Fig. 2a.17 / Link, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

18. Loop: in some typefaces, the bowl is created in the descender of the lowercase (G).

19. Serif: The right-angled or oblique foot at the end of the stroke.

20. Spine: The curved stem of the (S).

Fig. 2a.20 / Spine, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

22. Stress: The orientation of the letterform, indicated by the thin stroke in round forms.

Fig. 2a.22 / Stress, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

23. Swash: The flourish that extends the stroke of the letterform.

Fig. 2a.23 / Swash, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

24. Terminal: The self-contained finish of a stroke without a serif. This is something of a catch-all term.

- (T) above

- Flared

- Acute

- (t) above

- Grave

- Concave

- Convex

- Rounded as a ball or a teardrop.

Fig. 2a.24 / Terminal, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

b. Typography: Basic/ The Font

The full font of a typeface contains much more than 26 letters, numerals, and a few punctuation marks.

1. Uppercase: Capital letters, including certain accented vowels.

Fig. 2b.1 / Uppercase, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

2. Lowercase: Lowercase letters, include the same character as uppercase.

Fig. 2b.2 / Lowercase, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

3. Small Capitals: Uppercase letterforms draw to the x-height of the typeface. Small Caps are primarily found In serif fonts as part of what is often (expert set). Usually, use acronyms without making the typeface too messy.

Fig. 2b.3 / Small Capitals, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

4. Uppercase Numerals: also called lining figures. Used with tabular material or in any situation that calls for uppercase letters.

Fig. 2b.4 / Uppercase Numerals, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

Fig. 2b.5 / Lowercase Numerals, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

6. Italic: Most fonts today are produced with a matching italic. Small caps, however, are almost always the only roman.

Fig. 2b.6 / Italic, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

7. Punctuation, Miscellaneous Characters: Although all fonts contain standard punctuation marks, miscellaneous characters can change typeface to typeface.

Fig. 2b.7 / Punctuation, Miscellaneous Character, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

8. Ornaments: Used as flourishes in invitations or certificates (usually are provided as a font in larger typeface family).

Fig. 2b.8 / Ornaments, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

c. Typography: Basic / Describing Typefaces

Once you can recognize the parts of a letterform, you can apply what you

know to identify different typefaces.

1. Roman: The letterform is so-called because the uppercase

forms are derived from inscriptions of Roman monuments. A slightly lighter

stroke in roman is known as 'book'.

2. Italic: Named for fifteenth-century Italian handwriting on

which the forms are based.

Oblique: conversely

are based on the roman form of the typeface.

Fig. 2c.2 / Italic Oblique, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

Fig. 2c.5 / Condonse, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

6. Extended: An extended variation of a roman font.

The typefaces mentioned in the following slide represent 500 years of type design. The men and women who rendered them all sought to achieve two goals: easy readability and an appropriate expression of contemporary aesthetics.

d. Typography: Basic / Comparing Typefaces

For our

purposes, what is worth noting is not the similarities among these

typefaces, but their differences (each unique, compare). Beyond the gross

differences in x-height, these forms display a wealth of variety in the line

weight, relative stroke width and other internal relationships, and in

feeling.

The

uppercase R (above) displays the range of attitude typefaces are capable of

conveying. id you examine these forms long enough, you are bound to decide

that some of the tails seem more whimsical, some more stately; some will

appear more mechanical, some more calligraphic, some harmonious, some

awkward. As much as anything, what this examination tells you is how you

feel about the type and specific typefaces.

3. WEEK 3 - Lectures

a. Typography: Text / Tracking: Kerning and Letterspacing

The term ‘kerning’ refers to the automatic adjustment of space between

letters. It is often mistakenly referred to as ‘letterspacing. In

fact, letterspacing means adding space between the letters. The

addition and removal of space in a word or sentence are referred to as

‘tracking’.

Fig. 3a.1 / Kerning, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

Normal tracking, loose tracking and tight tracking

Fig. 3a.3 / Tracking, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

Designers always letter space uppercase letters, but there has long been

strong resistance within the type community to letterspacing lowercase

letters within text.

Fig. 3a.4 / LetterSpace, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

Fig. 3a.6 / Tight Tracking, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

b. Typography: Text / Formating Text

Flush left: This format most closely mirrors the asymmetrical experience of handwriting. Each line starts at the same point but ends wherever the last word on the line ends. Spaces between words are consistent throughout the text, allowing the type to create an even grey value.

Centered: This format imposes symmetry upon the text, assigning

equal value and weight to both ends of any line. It transforms fields

of text into shapes, thereby adding a pictorial quality to the

material that is non-pictorial by nature. Because centred type creates

such a strong shape on the page, it's important to amend line breaks

so that the text does not appear too jagged.

Flush right: This format places emphasis on the end of a line

as opposed to its start. It can be useful in situations (like

captions) where the relationship between text and image might be

ambiguous without a strong orientation to the right.

Fig. 3b.3 / Flush Right, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

Justified: Like centring, this format imposes a symmetrical

shape on the text. It is achieved by expanding or reducing spaces

between words and, sometimes, between letters. The resulting openness

of lines can occasionally produce ‘rivers’ of white space running

vertically through the text.

Fig. 3b.4 / Justified, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

Type that calls attention to itself before the reader can get to the

actual words is simply interference and should be avoided. Quite

simply if you see the type before you see the words, change

the

type.

c. Typography: Text / Texture

A type with a relatively generous x-height or relatively heavy stroke

width produces a darker mass on the page than a type with a relatively

smaller x-height or lighter stroke. Sensitivity to these differences in

colour is fundamental for creating successful layouts.

Fig. 3c.4 / Bauer Bodoni and Adobe Janson Pro, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

d. Typography: Text / Leading and Line Lenght

Type size: Text type should be large enough to be read easily at

arm's length—imagine yourself holding a book in your lap.

Leading: Text that is set too tightly encourages vertical eye

movement; a reader can easily lose his or her place. A type that is set

too loosely creates striped patterns that distract the reader from the

material at hand.

Line Length: Appropriate leading for text is as much a function

of the line length as it is a question of type size and leading. Shorter

lines require less leading; longer lines more. A good rule of thumb is

to keep line length between 55-65 characters. Extremely long or short

lines lengths impairs reading.

Fig. 3d.2 / Adobe Jenson, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

e. Typography: Text / Type Specimen Book

A type specimen book shows samples of typefaces in various different

sizes. Without printed pages showing samples of typefaces at different

sizes, no one can make a reasonable choice of type. You only determine

choice on screen when its final version is to read on-screen. A type

specimen book (or ebook for the screen) is to provide an accurate

reference for type, type size, type leading, type line length etc.

Fig. 3d.3 / Sample Type Specimen Sheet, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

Compositional requirement: Text should create a field that can

occupy a page or a screen. Think of your ideal text as having a

middle grey value (on the left, in the diagram on the next slide),

not a series of stripes (as seen of the one on the right).

4. WEEK 4 - Lectures

a. Typography: Indicating Paragraphs

In the first example, we see the ‘pilcrow’ (¶), a holdover

from medieval manuscripts seldom use today.

Fig. 4a.1 / Pilcrow, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

The example here displays a ‘line space’ (leading*) between

the paragraphs. Hence if the line space is 12pt, then the

paragraph space is 12pt. This ensures cross-alignment across

columns of text.

Fig. 4a.3 / Line Space Vs Leading, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

The example here displays the standard indentation. Typically

here the indent is the same size of the line spacing or the same as

the point size of your text.

The method of extended paragraphs below creates

unusually wide columns of text. Despite these problems,

there can be strong compositional or functional reasons for

choosing it.

b. Typography: Indicating Widows and Orphans

Fig. 4b.1 / Widow and Orphan, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

In justified text, both widows and orphans are considered serious

gaffes. Flush right and ragged left text are somewhat more

forgiving towards widows, but only a bit. Orphans remain

unpardonable. The only solution to widows is to rebreak your line

endings throughout your paragraph so that the last line of any

paragraph is not noticeably short. Orphans, you might expect,

require more care. Careful typographers make sure that no column

of text starts with the last line of the preceding paragraph.

c. Typography: Highlighting Text

c. Typography: Highlighting Text

The following are some simple examples of how to

highlight text within a column of text. Different kinds

of emphasis require different kinds of contrast.

Fig. 4c.2 / Different Emphasis, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

In this example, the sans serif font (Univers) has been

reduced by .5 to match the x-height of the serif typeface. 8 ≠

7.5

Fig. 4c.3 / Sans Serif Font - Univers, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

Also take note, when highlighting text by placing a field of

colour at the back of the text, maintaining the left reading

axis (right example) of the text ensures readability is at

its best.

Fig. 4c.4 / Colour Back of the Text, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

Sometimes it is necessary to place certain typographic

elements outside the left margin of a column of type

(extending as opposed to indenting) to maintain a strong

reading axis

Quotation marks, like bullets, can create a clear

indent, breaking the left reading axis. Compare the

indented quote at the top with the extended quote at the

bottom.

d. Typography: Headline within Text

There are many kinds of subdivisions within the text of a chapter. In the following visuals, these have been labelled (A, B and C) according to the level of importance. A typographers task is to make sure these heads clearly signify to the reader the relative importance within the text and to their relationship to each other.

There are many kinds of subdivisions within the text of a chapter. In the following visuals, these have been labelled (A, B and C) according to the level of importance. A typographers task is to make sure these heads clearly signify to the reader the relative importance within the text and to their relationship to each other.

A head indicates a clear break between the

topics within a section. In the following examples,

‘A’ heads are set larger than the text, in small

caps and in bold. The fourth example shows an A head

‘extended’ to the left of the text.

The B head here is subordinate to A heads. B

heads indicate a new supporting argument or example

for the topic at hand. As such they should not

interrupt the text as strongly as A heads do. Here the

B heads are shown in small caps, italic, bold serif,

and bold san serif.

The C heads, although not common, highlights

specific facets of material within B head text. They

not materially interrupt the flow of reading. As with

B heads, these C heads are shown in small caps,

italics, serif bold and san serif bold. C heads in

this configuration are followed by at least an em

space for visual separation.

Putting together a sequence of subheads = hierarchy.

Obviously, there is no single way to express hierarchy

within the text; in fact, the possibilities are

virtually limitless.

e. Typography: Cross Alignment

Cross aligning headlines and captions with text type reinforces the architectural sense of the page—the structure—while articulating the complimentary vertical rhythms. In this example, four lines of caption type (leaded 9 pts.) cross-align with three lines of text type (leaded to 13.5pts).

Cross aligning headlines and captions with text type reinforces the architectural sense of the page—the structure—while articulating the complimentary vertical rhythms. In this example, four lines of caption type (leaded 9 pts.) cross-align with three lines of text type (leaded to 13.5pts).

Below, one line of headline type cross-aligns with two

lines of text type, and (right; bottom left) four

lines of headline type cross-align with five lines of

text type.

💁♀️: Lectures 5 to 6 completed in Task 2.

INSTRUCTIONS

<iframe

src="https://drive.google.com/file/d/1IU579rmoOSTlxMggAhc4KIvTATiBU7EP/preview"

width="640" height="480" allow="autoplay"></iframe>

a. Task 1: Exercise 1 - Type Ekspression

For exercise 1, we are given some words to create type expressions. Those

words are Terror, Space, Glitch, Water, Broken, Abyss, Bark, and Colossal.

We need to choose Terror and 3 words out of 8 words. For each of the

words, we need to create a minimum of 3 sketches, it can be traditional

and digital drawing. No graphical elements are allowed, we are limited to only 10 typefaces

which are Adobe Caslon Pro, Bembo Std, Bodoni Std, Futura Std, Gill Sans

Std, ICT Garamond Std, ICT New Baskerville Std, Janson Text LT Std, Serifa

Std, and Univers LT Std.

Here are my sketches:

1. Rough Sketches (Traditional)

2. Clean Sketches (Digital)

Fig. 3a.2 / Clean Sketches or Digital, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

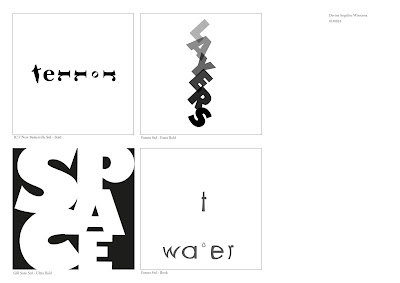

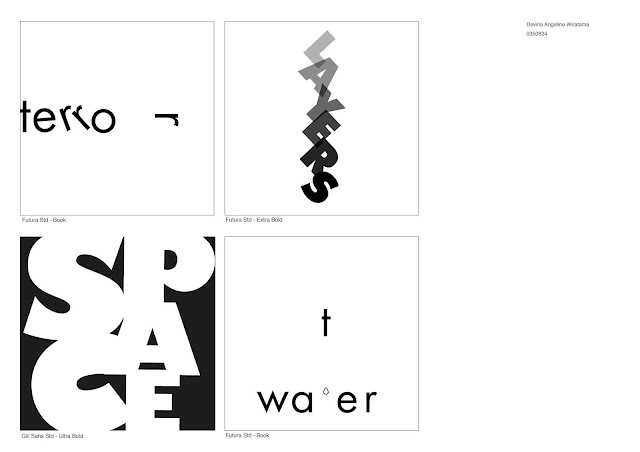

Words I chose: Terror, Layers, Space, and Water. The first one is

my rough sketches which are I drew on paper. The second is my clean

sketches, I drew on digital on Procreate. I personally like sketch

Terror#1, Layers#2, Space#1, and Water#2.

Here are my sketches:

2. Clean Sketches (Digital)

Fig. 3a.2 / Clean Sketches or Digital, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

Words I chose: Terror, Layers, Space, and Water. The first one is my rough sketches which are I drew on paper. The second is my clean sketches, I drew on digital on Procreate. I personally like sketch Terror#1, Layers#2, Space#1, and Water#2.

For the first word, "Terror", I used ICT New Baskerville Std - Bold. I wanted to create some guns with "r" words. I flip the "r" letters horizontal and rotate into -90°. I make the "o" letter smaller than else because I wanted to create it like a bullet.

For the second word, "Layers", I used Futura Std - Extra Bold. I wanted

to create something like layering. So, I reduce the opacity or change

the colour, <100% opacity into 100% opacity (up-down). It's like

going into deeper "layers".

For the third word, "Space", I used Gill Sans Std - Ultra Bold. I

wanted to utilize the positive and negative space. I coloured the artboard into black colour and the word itself is white colour.

Fig. 3a.6 / Water, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

For the

last word, "Water", I used Futura Std - Book. I wanted to describe how

there is a drop of water that falls from a water faucet into a puddle of

water. I separated the "wa er" and the "t". I gave the fisheye effect to

the word "wa er". I put a small circle in the bottom on "t" and gave both

of them a squishing effect. As the result, the circle shape squishing like

a water drop. Here's the first attempt in JPG.

Fig. 3a.7 / First Attempt JPG, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

4. Finale Outcome (Adobe Illustrator)

Mr Vinod suggested I change the typeface into Futura

Std, so the "gun" from "r" is simpler. Also, for the "water" no need to

be distorted. I changed the "water" and recreate the new "terror". Here

is the final outcome in JPG.

Fig. 3a.8 / Final Outcome JPG, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

Here is the final outcome in PDF.

<iframe

src="https://drive.google.com/file/d/1nXsVB2RzTN8tyGdsDDLgiKSkQ4KXHvxY/preview"

width="640" height="480" allow="autoplay"></iframe>

5. Type Expression: Animation

Mr Vinod

demonstrated how to create a basic type of animation using Illustrator and

Photoshop. This is my first animation demo.

This is my second attempt at type

animation.

I'm quite

like my second attempt. I wanted to create the last "r" it'll be a gun.

The letter "o" and the second "r" are dying. The last word, "ter" is avoiding. Here's my timeline in Adobe Illustrator.

I used

the red box on the left side as a guide so each of my words stay stable in

the middle of the artboard. This is my third attempt at type

animation.

Fig. 3a.12 / Third Type Animation, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

I put

more "pause" time when the "r" becomes a gun like Mr Vinod said. So,

people can recognize them clearly. I feel the "O" is a little bit odd so I tried to create again.

This is my fourth attempt at type animation.

I

decided to make the "O" and "R" when dying they'll fall off. It's like they walk in the rope, if unstable, they will die. I like it. I hope

I'm not recreating again.

Final Animated Type Expression

b. Task 1: Exercise 2 - Text Formating

First, we need to watch video 3, video 4, ex text formatting 1:4, 2:4, 3:4, 4:4, and 4:4A. In exercise 2, we learnt about how to create one final layout addressing different areas of text formatting, for example kerning, leading, paragraph spacing, alignment, etc. We used Adobe Indesign for this exercise. This exercise helps us to demonstrate the use of Grids, layouts and page flow and to apply the necessary skills and sensibilities for effective typographic communication.

Lecture 1:4 - Text Formatting: Kerning and TrackingIn this section, we learnt how to create a new document in InDesign and insert the text with only 10 typefaces that are provided by Mr Vinod.Here is the text formating without kerning.

Here is the text formating with kerning.

And here is the text formating comparison between w/ kerning and w/o kerning.

Lecture 2:4

Here are the notes that I took from the video.

Notes:

- A good page layout is heavily dependent on an attractive margin space- Point size within A4 and A3 is generally between 8 to 12 points- Use 10 typefaces that are provided- A-line length or number of characters (under info) always be about 55 to 65- Take note of your leading size- Separate the heading and sub-heading on the left side- Size of the leading is equal to paragraph spacing bellow (under paragraph control)- Keep text width the same for the same text of information. If they differ it confuses the audience, making them think it's a separate piece of information.- See whether the positive and negative space has to be equal (middle grey value)

Here's the progress.

Lecture 3:4

Here are the notes that I took from the video.Notes:

- Alignment and raging.- Before beginning the design of anything, you must understand the different levels of information that are contained within the document.- Place the picture. - Whenever you're dealing with information, which is body text, you cannot have different sizes of text width.- Before you make kerning and letter adjustments, you need to make sure that your InDesign kerning/ tracking must be 5/ 1000 em.- You can use left align, left justify, and centre justify.- Don't use central alignment and right alignment.- If you use left justify, check the hyphenate and try to reduce the hyphenation using letter spacing and kerning, and take note the column interval needs to be increased from 5-7 mm, or sometimes 10 mm.

Here's the progress.

Lecture 4:4

Here are the notes that I took from the video.Notes:- Cross alignment and baseline grids.- Sometimes headlights can be outside of the body text because it's not the major part of the text field. The major part of the text field is always the body text.- Headings: Double point size and leading of body text.- Sub-headline make it italic/ oblique.- View > Grids & guides > Show baseline grid (zoom in to see it).- Adjust the baseline grid. Edit > Prefences > Grids > Increment (same number with size of the leading) > threshold (50%) > select the body text > (right click) select text frame options > Baseline options (offset: leading) > General (align: top).

Here's the progress.

Next, I made six texts formatting. Here are in the small picture.

I think the 7th is better in fig.3b.13 one. Here's the result.

Fig. 3b.15 / Last Text Formating, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

Make sure you fulfil this, Devina!

#Week4_202108 (Wednesday & Friday) Things to look out for when completing Exercise 2 of Task 1:- Font size (8–12)

- Line Length (55–65/50–60 characters)

- Text Leading (2, 2.5, 3 points larger than font size)

- Ragging (left alignment) / Rivers (Left Justification)

- Cross Alignment

- No Widows / Orphans

Fulfil the Instructions.

- Font size (9 pt)

- Line length (55-65 characters)

- Text leading (11.5 pt)

- Rivers (left justification)

- Cross alignment

- No widows/orphans

- The kerning is no more or less than +/- 3 (15)

Final Outcome

Final in JPG

Fig. 3b.17 / Final Outcome in JPG, Week 5 (09.24.2021)

Final in PDF

<iframe src="https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ADg8tpLlY1N8X5hcyCJESzxS47_VaQG8/preview" width="640" height="480" allow="autoplay"></iframe>

For the third word, "Space", I used Gill Sans Std - Ultra Bold. I wanted to utilize the positive and negative space. I coloured the artboard into black colour and the word itself is white colour.

Fig. 3a.6 / Water, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

Fig. 3a.7 / First Attempt JPG, Week 2 (09.03.2021)

4. Finale Outcome (Adobe Illustrator)Mr Vinod suggested I change the typeface into Futura Std, so the "gun" from "r" is simpler. Also, for the "water" no need to be distorted. I changed the "water" and recreate the new "terror". Here is the final outcome in JPG.

Fig. 3a.8 / Final Outcome JPG, Week 3 (09.10.2021)

Here is the final outcome in PDF.

<iframe

src="https://drive.google.com/file/d/1nXsVB2RzTN8tyGdsDDLgiKSkQ4KXHvxY/preview"

width="640" height="480" allow="autoplay"></iframe>

5. Type Expression: Animation

Mr Vinod demonstrated how to create a basic type of animation using Illustrator and Photoshop. This is my first animation demo.

I used the red box on the left side as a guide so each of my words stay stable in the middle of the artboard.

Fig. 3a.12 / Third Type Animation, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

I put

more "pause" time when the "r" becomes a gun like Mr Vinod said. So,

people can recognize them clearly. I feel the "O" is a little bit odd so I tried to create again.

This is my fourth attempt at type animation.

I

decided to make the "O" and "R" when dying they'll fall off. It's like they walk in the rope, if unstable, they will die. I like it. I hope

I'm not recreating again.

Final Animated Type Expression

Lecture 1:4 - Text Formatting: Kerning and Tracking

Lecture 2:4

Here are the notes that I took from the video.

Notes:

- A good page layout is heavily dependent on an attractive margin space

- Point size within A4 and A3 is generally between 8 to 12 points

- Use 10 typefaces that are provided

- A-line length or number of characters (under info) always be about 55 to 65

- Take note of your leading size

- Separate the heading and sub-heading on the left side

- Size of the leading is equal to paragraph spacing bellow (under paragraph control)

- Keep text width the same for the same text of information. If they differ it confuses the audience, making them think it's a separate piece of information.

- See whether the positive and negative space has to be equal (middle grey value)

Here's the progress.

Lecture 3:4

Here are the notes that I took from the video.

Notes:

- Alignment and raging.

- Before beginning the design of anything, you must understand the different levels of information that are contained within the document.

- Place the picture.

- Whenever you're dealing with information, which is body text, you cannot have different sizes of text width.

- Before you make kerning and letter adjustments, you need to make sure that your InDesign kerning/ tracking must be 5/ 1000 em.

- You can use left align, left justify, and centre justify.

- Don't use central alignment and right alignment.

- If you use left justify, check the hyphenate and try to reduce the hyphenation using letter spacing and kerning, and take note the column interval needs to be increased from 5-7 mm, or sometimes 10 mm.

Here's the progress.

Lecture 4:4

Here are the notes that I took from the video.

Notes:

- Cross alignment and baseline grids.

- Sometimes headlights can be outside of the body text because it's not the major part of the text field. The major part of the text field is always the body text.

- Headings: Double point size and leading of body text.

- Sub-headline make it italic/ oblique.

- View > Grids & guides > Show baseline grid (zoom in to see it).

- Adjust the baseline grid. Edit > Prefences > Grids > Increment (same number with size of the leading) > threshold (50%) > select the body text > (right click) select text frame options > Baseline options (offset: leading) > General (align: top).

Here's the progress.

Next, I made six texts formatting.

Here are in the small picture.

I think the 7th is better in fig.3b.13 one. Here's the result.

Make sure you fulfil this, Devina!

#Week4_202108 (Wednesday & Friday) Things to look out for when completing Exercise 2 of Task 1:

I think the 7th is better in fig.3b.13 one. Here's the result.

Fig. 3b.15 / Last Text Formating, Week 4 (09.17.2021)

Make sure you fulfil this, Devina!

#Week4_202108 (Wednesday & Friday) Things to look out for when completing Exercise 2 of Task 1:

- Font size (8–12)

- Line Length (55–65/50–60 characters)

- Text Leading (2, 2.5, 3 points larger than font size)

- Ragging (left alignment) / Rivers (Left Justification)

- Cross Alignment

- No Widows / Orphans

- Font size (9 pt)

- Line length (55-65 characters)

- Text leading (11.5 pt)

- Rivers (left justification)

- Cross alignment

- No widows/orphans

- The kerning is no more or less than +/- 3 (15)

Final in JPG

Fig. 3b.17 / Final Outcome in JPG, Week 5 (09.24.2021)

Final in PDF

<iframe src="https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ADg8tpLlY1N8X5hcyCJESzxS47_VaQG8/preview" width="640" height="480" allow="autoplay"></iframe>

FEEDBACK

Here are some questions to help to create the feedback (Type Expression)

- Are the explorations sufficient?

- Does the expression match the meaning of the word?

- On a scale of 1–5, how strong is the idea?

- How can the work be improved?

- Is the animation suitable?

- Does the animation reflect or enhance the meaning of the word?

- Does the animation reflect the form being expressed?

- Does the animation create a smile in your mind?

- How can it be improved?

Week 1: E-Portfolio Briefing

-

General Feedback

Please do not change your E-Portfolio with a different theme (if

you're not used to it) and black/ white background

-

Specific Feedback

Update the E-Portfolio with the embed, line/ horizontal rule,

and descriptions.

Week 2: Type Expression

- Exercise:

-

General Feedback

Height, thin-thick, big-small exaggerate more. Not much

feedback because we need to improve ourselves, not depend on

what the lecture said. It's your art and it's your

Journey.

-

Specific Feedback

Extremely careful how much distortion had been used, use very

min distort, focus on the text. Communication only through the

word/ understanding just using the word. Give more Depth

dimension in Layers' words.

- E-Blog:

-

General Feedback

Watch out for the themes, formating space (paragraph spacing,

force break), don't embed the sketches (embed is only for

MIB).

-

Specific Feedback

Update the further reading, reflection, and the date of

description. Take a picture with sunlight, not with a

lamp.

Week 3: Type Expression

-

General Feedback

No colour allow. Don't use too much distortion. Don't forget

to put the font description and name. Try not to choose the

wrong font

-

Specific Feedback

No need to distort the "t" in the "Water" word. Change the

font "terror" into Futura so the "r" can see as a gun.

Week 4: Type Expression and Animation

- Exercise:

-

General Feedback

Must use 10 typefaces. Try to convey to people with your

work.

-

Specific Feedback

Interesting and great work. Pause in the R when it becomes a

gun. The scenes need to be broken down into constituent parts

so that clearly understandable. The idea is excellent and the

execution is almost there.

- E-Blog:

-

General Feedback

Don't forget about the horizontal rule, headline lectures,

etc. No need date for the lectures. It is not compulsory to

add pictures to the lectures.

-

Specific Feedback

Use Helvetica font in the name and description in exercise 1.

Might see trxssah blog as a reference.

Week 5: Submission

- Exercise:

Good.

- E-Blog:

Excellent use of "Jump Links". All info present.

-

General Feedback

Please do not change your E-Portfolio with a different theme (if you're not used to it) and black/ white background

-

Specific Feedback

Update the E-Portfolio with the embed, line/ horizontal rule, and descriptions.

Week 2: Type Expression

- Exercise:

-

General Feedback

Height, thin-thick, big-small exaggerate more. Not much

feedback because we need to improve ourselves, not depend on

what the lecture said. It's your art and it's your

Journey.

-

Specific Feedback

Extremely careful how much distortion had been used, use very

min distort, focus on the text. Communication only through the

word/ understanding just using the word. Give more Depth

dimension in Layers' words.

Height, thin-thick, big-small exaggerate more. Not much feedback because we need to improve ourselves, not depend on what the lecture said. It's your art and it's your Journey.

Extremely careful how much distortion had been used, use very min distort, focus on the text. Communication only through the word/ understanding just using the word. Give more Depth dimension in Layers' words.

- E-Blog:

-

General Feedback

Watch out for the themes, formating space (paragraph spacing, force break), don't embed the sketches (embed is only for MIB).

-

Specific Feedback

Update the further reading, reflection, and the date of description. Take a picture with sunlight, not with a lamp.

Week 3: Type Expression

-

General Feedback

No colour allow. Don't use too much distortion. Don't forget to put the font description and name. Try not to choose the wrong font

-

Specific Feedback

No need to distort the "t" in the "Water" word. Change the font "terror" into Futura so the "r" can see as a gun.

- Exercise:

-

General Feedback

Must use 10 typefaces. Try to convey to people with your work.

-

Specific Feedback

Interesting and great work. Pause in the R when it becomes a gun. The scenes need to be broken down into constituent parts so that clearly understandable. The idea is excellent and the execution is almost there.

- E-Blog:

-

General Feedback

Don't forget about the horizontal rule, headline lectures, etc. No need date for the lectures. It is not compulsory to add pictures to the lectures.

-

Specific Feedback

Use Helvetica font in the name and description in exercise 1. Might see trxssah blog as a reference.

- Exercise:

Good. - E-Blog:

Excellent use of "Jump Links". All info present.

REFLECTION

Experience

I like how the lectures taught us coherently and clearly. Due to the

class often conveys things that are important and useful to me, it wasn’t

boring and I didn’t fall asleep. Every time before the class start, I was

always feeling anxious because there are a lot of things that I need to

finish and learn. I was greatly helped by the feedback from the

lecturers.

Observation

I observed that don’t give up if you haven’t tried. The subjects might

be a lot and tough let alone just starting uni-life, just do it. I

noticed that I had a struggle finding and borrow the book of typography

in the library in an online situation. I also examined that I had

trouble learning adobe in an online way.

Findings

I realized that typography is not as simple as I thought. there are many rules that must be followed and must be observed. very disciplined. I am grateful to be able to learn about typography because it is very useful for my blog, my work, and things in the future. I also learned about 10 typefaces where there is a good history behind them.

FURTHER READING

Fig. 4.1 / The Complete Manual of Typography (2011), source: The Complete Manual of Typography

Based on one of the requirements of this typography blog, I did some further

reading with the book "The Complete Manual of Typography, Second Edition" by

James Felici. This pdf book is Excellent! It tells us how the type should

look and how to set type like a professional. The writing is clear and

straightforward. I'm a bit surprised that it's free in pdf (I think it's

legal).

Chapter 1 "Typography Basics": What Makes Good Type Good (and Bad Type Bad)

- page 105.

James said, the goal here is not connoisseurship (although people who care

about type are often labelled “type snobs”) but rather knowing the rules of

the craft, so that the type you set serves the text and the reader in ways

they both deserve.

1. Legibility and Readability

1. Legibility and Readability

When most

people look at a page, they don’t see typefaces and they don’t see type.

They see words. They’re not admiring the page—they’re reading it, and

reading is all about rhythm. Legibility refers to a reader’s

ability to easily recognize letterforms and the word forms built from

them. Readability refers to the facility and comfort with which

text can be comprehended. Text with good readability must also be legible,

but mere legibility doesn’t make text readable.

Design—in the form of page size, type

size, and line length—also has a lot to do with legibility and

readability. Paperback editions of hardbound books often suffer from

this problem because cheapskate publishers simply reduce the larger

hardbound pages photographically and print them in

a smaller paperback format. Ultimately, though, the most poorly set type

isn’t illegible or even unreadable; it’s just carelessly set.

2. Type Colour

2. Type Colour

When

this texture is consistent and even, the type is said to have good

colour. The tightly spaced type will have a darker colour than the

loosely spaced type, but the most important thing is for the colour to

be even and consistent. Alternately tight and loose lines are a colour

problem at a very “local” level, but colour problems are most

noticeable at a larger scale.

Such

variations in colour don’t necessarily affect readability, but they

are a distraction. When one dark paragraph stands out on a page, it

catches your eye. This shouldn’t happen. Variations in colour like

this give the impression of a lack of quality control, a lack of care,

a lack of expertise. It gives the text a slack and unkempt

appearance.

3. Overly Tight Facing

3. Overly Tight Facing

Tight spacing interferes with the

reader’s ability to recognize word forms. Readers who have to do a

double-take to recognize a word or phrase are at once slowed down

and annoyed. An rn that melts together to look like an m, a; cl that

looks like a d; or vv that looks like a w is bound to trip people

up. More generally, in tightly spaced text, character-sequence

patterns that are usually easy to recognize become unfamiliar, and

readers are forced back toward reading letter by letter, as if in a

foreign language.

4. Overly Loose Spacing

4. Overly Loose Spacing

The strategy is based on the

ability of the eye to pick out differences between tight and

tighter types more easily than between loose and looser types. In

other words, loosely spaced type more readily creates a sense of

consistent type colour—even though that colour is quite

pale—because tight lines aren’t allowed and everything is set so

loose that the loosest lines don’t stand out. Typeset this way is

not a pretty sight, but it does have the practical benefit of

always looking the same, and everyday composition problems are

masked by the slack spacing.

Comments

Post a Comment